NGOs, your PH slips are showing

In the realm of human rights advocacy, the objectivity and impartiality of NGOs play a crucial role.

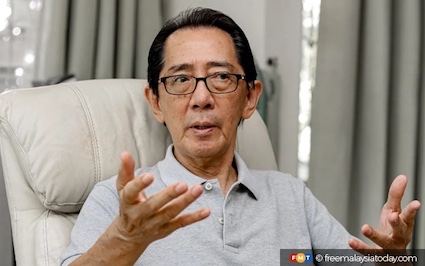

From Kua Kia Soong, Free Malaysia Today

With six states set for elections within weeks, Selangor has been ranked as the most democratic state in Malaysia by institutional reform advocacy group CSO Platform for Reform. A few days ago, the Perikatan Nasional (PN) coalition was criticised by the NGOs for its authoritarian rule during the pandemic.

I understand a “patriotic” group of NGOs will soon be calling for “national unity” just before the state elections. This has nothing to do with supporting the so-called “unity government”, of course!

In the group’s “Malaysian Democracy League” unveiled recently, Selangor was top among 12 states, with a score of 69%, while Perlis came in last at 34%.

A total of 14 parameters were used to determine the scores for each state assembly. Among the parameters were the formation of a special select committee and public accounts committee (PAC) at state level; public hearing of PAC meetings and appointment of PAC chairman from the opposition; chief minister’s question time; introduction of a shadow Cabinet; anti-hopping legislation; duration of assembly sittings; number of backbenchers and recognition of the opposition leader, and fair allocations for elected representatives.

In the realm of human rights advocacy, the objectivity and impartiality of NGOs, or non-governmental organisations, play a crucial role. Their ability to objectively assess and criticise governments is essential in fostering a fair and democratic society.

However, recent claims by certain human rights NGOs in Malaysia raise concerns about their alleged partiality towards the Pakatan Harapan (PH) coalition, particularly in the state of Selangor. This article aims to shed light on the indices used by these NGOs to judge different states and explore the potential implications of their bias.

Objectivity and fairness of these indices

Human rights NGOs have claimed that Selangor is the most democratic state in Malaysia. While the definition of democracy may vary, these organisations have purportedly utilised certain indices to support their assertions.

However, it is crucial to examine the objectivity and fairness of these indices to ensure a comprehensive analysis.

Electoral performance: One possible index used to judge democratic credentials is electoral performance, such as voter turnout and fair representation.

However, it is important to note that a high voter turnout does not necessarily reflect the strength of democracy but could indicate various socio-political factors.

Freedom of speech and assembly: The freedom to express opinions and gather peacefully is a cornerstone of democracy. NGOs might evaluate the level of freedom of speech and assembly by examining instances of censorship, restrictions on media, and government response to peaceful protests.

Civil society engagement: A vibrant civil society is indicative of a healthy democratic environment. NGOs might consider the degree of engagement between civil society organisations (CSOs) and the state government, including consultations, policy dialogues, and public participation in decision-making processes.

Government transparency: Transparency and accountability are essential in a democratic society. NGOs may assess the level of transparency in governance, including access to information, financial disclosures, and the implementation of anti-corruption measures.

People before profits: Which state is more attentive to the needs of the people, the environment, and sustainable growth? Are the state governments more beholden to the interests of corporate players or the interests of the people and environment?

Local democracy: Which state has initiated local government elections, the most important index of third-tier democracy, a democratic right that Malaysians have been deprived of since 1965?

Alleged partiality of NGOs

Despite the importance of objectivity and impartiality in assessing democratic credentials, concerns have been raised about certain human rights NGOs favouring the PH coalition, particularly in Selangor. This alleged partiality can be attributed to several factors:

Historical affiliation: NGOs may have established relationships with political parties over time, leading to perceptions of bias. In the case of Selangor, PH held power from 2008 to 2020, potentially influencing NGO perceptions and relationships.

Funding sources: NGOs often rely on external funding, which may come from various sources. If there is a perception that funding is influenced by political affiliations, it can raise doubts about the objectivity of the NGOs involved.

The limited scope of assessment: NGOs may focus primarily on specific indicators, neglecting a comprehensive evaluation of other crucial aspects of democracy. Such a limited scope can skew the overall assessment and reinforce bias.

The co-option of NGO activists by PH: The co-option of NGO activists by PH following the recent elections highlights the potential implications of this phenomenon on the credibility of human rights advocacy.

Political appointments: The PH coalition, upon assuming power, made political appointments that included individuals with NGO backgrounds. While such appointments may be aimed at promoting expertise and experience, they raise questions about the independence and objectivity of those individuals in their new roles.

Funding and resources: The access to funding and resources provided by the PH-led government can create a dependency among certain NGOs, potentially compromising their ability to maintain impartiality. The allocation of resources may inadvertently influence the agenda and priorities of these organisations, blurring the lines between advocacy and political alignment.

Consultation and collaboration: Collaboration between the government and NGOs is essential in policy development and implementation. However, when NGOs are co-opted into the government machinery without adequate safeguards, it raises concerns about their ability to critically engage and hold the government accountable.

Implications of NGO co-option by PH

Co-option can lead to a loss of independence for NGOs, compromising their ability to objectively assess government policies and actions. This erosion of independence weakens their role as watchdogs and diminishes their credibility in advocating for human rights.

When activists aligned with the ruling coalition occupy influential positions within NGOs, it can discourage critical assessment and constructive criticism of government policies.

This lack of diverse perspectives can hinder the development of a robust and inclusive democratic discourse.

Thirdly, co-option can contribute to polarisation by creating a perception that NGOs are aligned with a specific political party. This perception can result in limited discourse and hinder the formation of inclusive alliances and coalitions aimed at advancing human rights and democratic principles.

Only through a truly independent and impartial civil society can Malaysia foster a thriving democracy that upholds the rights and aspirations of all its citizens.

The objectivity and impartiality of human rights NGOs are vital for the promotion and protection of democratic values. While NGOs play a crucial role in monitoring governments and advocating for human rights, allegations of partiality must be taken seriously.

It is essential for NGOs to ensure that their assessments and judgements are founded on comprehensive and objective criteria, free from political influence.

So, by addressing concerns of partiality, NGOs can strengthen their credibility and contribute to the development of a truly democratic society in Malaysia.

Kua Kia Soong is a former MP for Petaling Jaya and former director of rights group Suaram.