Lam Thye breaks 32-year silence

Wong Chun Wai, The Star

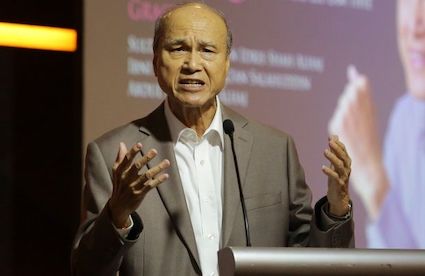

IT has taken more than three decades for former DAP stalwart Tan Sri Lee Lam Thye to break his silence on the reason he took the drastic step of quitting from the party that was his entire political life.

In his newly-released memoir, Call Lee Lam Thye – Recalling a Lifetime of Service, the legendary former Member of Parliament for Bukit Bintang wrote of how he endured unbearable internal politics, including relentless allegations.

It’s obvious now that his style of moderate politics neither sat well with the rhetoric nor gelled with the thunder and lightning approach of his other DAP comrades, which remains a party trademark.

“My style of politics did not go down well with many of my party bosses and colleagues who felt that I was spending more time for the electorate than fixing the DAP.

“Being an Opposition member, I perceived my role as a constructive opposition offering constructive criticism and alternative suggestions for the consideration of the government,” he said, adding that “my non-belligerent approach did not go down well and there were criticisms against my stance on various issues”.

The differences were simmering but the straw that broke the camel’s back, according to Lee, was when, in the run-up to the 1990 general election, he was informed by the party leadership that he would be removed from Bukit Bintang, which he had served for four terms.

He was commissioned to a different constituency but “I was not even told where I would be fielded instead”.

Lee said he disagreed with the party decision, insisting he should remain “unless, of course, I had not performed, was a liability or I had been involved in some scandal”.

Lee suspected that the decision to take him out of Bukit Bintang went beyond stopping him from defending his constituency, saying he sensed it was something sinister. As his appeals fell on deaf ears, Lee described it as “agonising because I did not know which place or state I would be fielded, and the general election was just around the corner”.

The DAP stronghold was eventually contested by lawyer Wee Choo Keong, who also left the party in the end.

On Sept 29, 1990, Lee, who was a DAP deputy secretary-general, stunned the nation when he announced his decision to quit but offered no reasons. The silence, however, shifted the gears in the rumour mill to high.

He was accused of selling out to Barisan Nasional. His wife was also blamed for having a gambling addiction and had to be bailed out for incurring huge debts at the casino in Genting Highlands.

Interestingly, former DAP secretary-general Lim Kit Siang, who delivered the bad news to Lee, has not spoken about the decision to take the latter out of Bukit Bintang.

But Lee must have finally decided to fill this gap in history as time has a way of healing old wounds, no matter how deep, and the degree of bitterness and anger would have diminished.

In the end, these unhappy episodes remain in the past, providing students of history and politics with better insight of what transpired in our nation’s political history.

It’s hard to be sure how many young Malaysians know Lee or are clued in to what he has shared.

But it’s good that both Lim and Lee have decided to talk about their journeys in the country’s history through their autobiographies. Lim, or Kit as he’s called, is 81 years old while Lee is 75.

Lee has always been a different kind of Opposition MP. His devotion to constituency services has been a boon and bane. He was on call 24/7 and took helping his electorate seriously while his Opposition colleagues sneered at him, saying this was City Hall’s job, and not an MP’s.

Many preferred to be popular by issuing press statements and displaying their fire-brand bravado at rallies.

Ironically, while the DAP grappled with the problem of getting accepted by the Malay voters, even till now, Lee had no issue getting Malay votes, presumably because of his non-antagonistic approach.

Former New Straits Times group editor, the late Datuk Ahmad A. Talib, once wrote that a popular quote among Malay voters in the 1970s was “kalau Lee Lam Thye lawan di Kampung Baru pun dia boleh menang” (if Lee Lam Thye contests in Kampung Baru, a predominantly Malay area, he could still win).

Basically, it was an acknowledgement that Lee, despite being a DAP leader, could still be accepted by the Malays.

I have heard of Muslims going to seek Lee’s help because they weren’t able to secure a place with Tabung Haji to perform their haj!

While most politicians cease serving the people after leaving public office, Lee has continued to do so in various capacities in non-governmental organisations.

Preferring to call himself a social activist, in his post-DAP life, he continues like he never left, by issuing regular press statements to the media – even though many who had covered him as reporters have either retired – or expired!

The younger news editors, who’ve never known Lee, are likely to be less patient with this legend.

But Lee has certainly left a mark in Malaysia’s parliamentary and political history. It’s safe to say that no lawmaker has been able to match his legacy. The lanky and gentle Lee will be known for his moderate views and consistent call for national unity.

One glaring missing part in the book is Lee’s decades of experience as a DAP leader and MP. Surely, there would be much he could shed light on as the DAP was his only political home. The result is a missing chunk of record.

Interestingly, Lee spoke of how his involvement with politics began with a letter he wrote to the late Lee Kuan Yew when the former was a school leaver, who had just started work in Ipoh.

Lee received no reply but one day, CV Nair – who went on to become the MP for Bangsar and president of Singapore – arrived in Ipoh to meet him.

He helped form the DAP, an offshoot of PAP, and following the Malaysia-Singapore split in 1965, was recruited to join the National Union of Commercial Workers as executive secretary in 1968. He was then just 22 years old.

That was his first step into politics.

In summary, the 300-page book is a record of a Malaysian patriot, who was always there for the people who needed him most and constantly made himself available.