Malaysia’s economic life: not sick but dying

RAMAN LETCHUMANAN, MALAYSIAKINI

On Feb 1, Fitch Solutions reported a worsening economic outlook, a downgrade of GDP growth from 11.5 to 10 percent amidst strained government finances.

In early Dec 2020, Fitch Ratings downgraded Malaysia’s IDR from A- to BBB+, making it more expensive to borrow, citing lingering political wrangling and uncertain prospects for improving governance.

In between, Transparency International (TI) released its Corruption Perception Index (CPI), which saw Malaysia losing two score points and dropping six rungs in ranking in 2020 compared to 2019.

The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (Unctad) reported that FDI in-flows to Southeast Asia fell by 31 percent on average, but Malaysia’s fell by 68 percent – more than double the regional average.

Unctad also reported that the global FDI fell by 42 percent, but in developing economies only by 12 percent. Bucking the trend is China, where it increased by four percent, and India by 13 percent, boosted by the digital sector.

Reportedly, Malaysia is not only the worst performer in Asean, but globally. Another feather-in-the-cap, along with other shameful global ratings mentioned above.

The public, as they tolerate dire day-to-day living conditions, is not surprised, except that these macro statistics seem so detached from reality. But what is shocking is the government’s response of complete denial, even painting a rosy picture of the economy.

This is compounded by the opposition’s knee-jerk reaction raising a maelstrom of attacks against the government each time such reports appear, but short of any thought-out alternatives. All are interested only in political capital, not economic or social capital.

Somehow, the relevant institutions, economists, analysts have mostly mirrored their reactions based on the political divide, hardly offering in-depth independent analysis.

To me, the economy is not just sick, but dying. I will justify this using basic economics and personal experiences on the ground, looking deeper beyond these headline numbers. Likewise, I welcome reasoned factual discourse to my thoughts here. I would love to be proven wrong.

In the midst of all these depressing global rankings, the government rallied for a state of national emergency, purportedly to save the “economic life” of the nation due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Isn’t this akin to pulling out the life-support system of a dying patient?

Corruption on the precipice

Behind the CPI score and ranking emerges a scary scenario. Just look at the countries below Malaysia. Even Rwanda is eight rungs above us at 49.

Malaysia seems to be at the edge of a cliff separating the good and the bad, and even a slight drop in score will take us down the deep incline to the ugly.

Keep in mind that CPI is based on the perception among selected target groups, not a measure of actual corruption.

The ranking in 2020 was buffered by the dramatic rise in confidence in 2019 under Pakatan Harapan.

The final months of 2020 and just one month into 2021 gives a clear indication of what may happen in 2021.

It is widely speculated that power and positions are traded, and some of the accused discharged without trial, just to keep the government intact; but that is not recognised as corruption.

The more political instability there is, the more public funds are used to buy support, and the corresponding decline in good governance. Already, we hear rumblings of mismanagement and misappropriation by these political appointees in government and government-linked entities.

Malaysia continues to be deluded with self-praise in comparison with other Asean countries, especially Indonesia. I worked and lived in Indonesia for 14 years, and have regularly visited the other countries as part of my job. In reality, the vast improvement in Indonesia’s anti-corruption measures has not been adequately captured by TI.

Indonesia comes down hard on the ruling class and elites who indulge in corruption. Once named as a “suspect” based on preliminary investigations, they are summoned and immediately detained without bail.

Within months, the guilty are convicted and harsh jail terms imposed. In fact, one suspect was on the run for a long time, apparently living a good life in Malaysia.

The perception of Indonesia is that corruption is prevalent among the masses, but they fail to understand that because of low wages, almost everyone indulges in “additional work” and the payment for their “services”.

Expatriates complain having to pay a dollar to the street attendants who find a parking spot for free, act as car jockeys and control traffic; but they willingly pay several times over in parking charges in their own country.

Civil servants tell me they hardly check their salaries banked in because it’s just pittance. Once such long-held sticky perception is factored in, and as these countries develop, they would easily overtake Malaysia in no time. Otherwise, how does one explain China (CPI rank 78), India (86), and Indonesia (102) doing so well in FDI?

Yet, what was our government’s response? Simply citing the anti-corruption measures put in place by Harapan, which they ousted, claiming it to be unfit to govern; and that the “rule of law will be strictly applied to everyone”. This even in the face of many VIPs openly violating the Covid-19 SOPs and getting away with it.

Economy bleeding

Economic growth is not about plucking money from trees or printing money. Classical economics of the early 1800s talked about land, labour and capital as the three primary factors of production.

As technology, skills and entrepreneurship enhanced, these morphed into resources, social capital and financial clout. In terms of technological trajectory, economic growth advanced from resource extraction to manufacturing and services, enabled by creative destruction in industrial structure based on biotechnology, microelectronics, ICT and the current 4th Industrial Revolution.

In response to the warnings of stalling economic growth, the government took out full-page colour advertorials claiming investors’ confidence remains encouraging and external trade shows resilience.

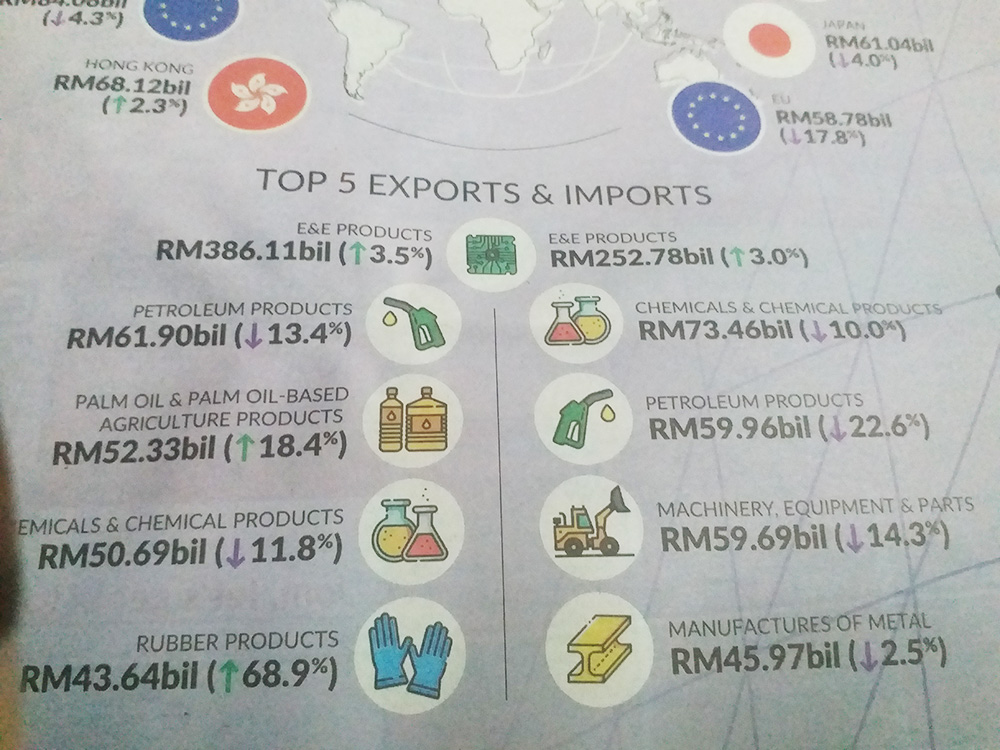

Supposedly, this claim is fortified by a Top 5 Exports and Imports chart[1]. The Top 5 exports are E&E, petroleum, palm oil, chemicals and rubber products; whereas the Top 5 imports are EE, chemicals, petroleum, machinery and metal manufactures.

The Statistics Department reported that Malaysia recorded “highest exports of RM95.7 billion in Dec 2020, with re-exports contributing 18.4 percent; while imports declined for intermediate goods (five percent) and capital goods by two percent”. Trade is a good proxy for the quality of FDI.

Given the limited space here, let me highlight just a few points. For one, our top exports are mainly labour-intensive assembly operations and resource-based or extraction; while imports are manufactures or intermediate goods.

About 20 percent of the exports are re-exports, not something to be proud of. Declining imports of intermediate goods imply less value-add activity domestically.

It seems Malaysia’s industrial structure has gone back to the “land, labour and capital” factors of production.

No wonder we hear ever-increasing reports of destruction of pristine forests and water catchment areas for construction, mining and natural resource extraction.

Petroleum products, our biggest earner, are only sufficient for our own needs, with almost no net exports. Some cynically claim we are only good at exporting talents while suppressing talents that remain. So much for Vision 2020.

Rather than benefiting from the e-commerce driven economy, Malaysia is excelling in the low-end warehousing, logistics and delivery for foreign e-commerce platforms.

It is also hollowing out our manufacturing and commercial base, where foreign goods and services can be purchased online at a much lower cost and assured quality. It is heart-breaking to see street vendors plying everything from pizza to pickled mango, much like in Indonesia years ago.

Malaysia is fast losing its edge for low-cost assembly and manufacture. We depend exclusively on foreign labour but treat them like “slave” labour, rather than social capital. Major importers are now scrutinising our top exports based on our appalling labour practices.

Any rational investor will decide to locate where social capital is, rather than get caught up with imported labour and its myriad regulatory/enforcement hurdles.

My Indonesian friend, who develops high-end bungalows and shop offices in Jakarta, baulked at our minimum wage, saying he cannot even get locals for that salary.

He treats his workers and maids as a family and pays them cash wages every Saturday. He just cannot comprehend the many incidents of labour abuse in Malaysia. Cheap foreign labour may soon dry up.

It needs no imagination to predict how our economy will perform in 2021 amidst the nationwide lock-down, emergency and constant political wrangling.

Fiscals sucked dry

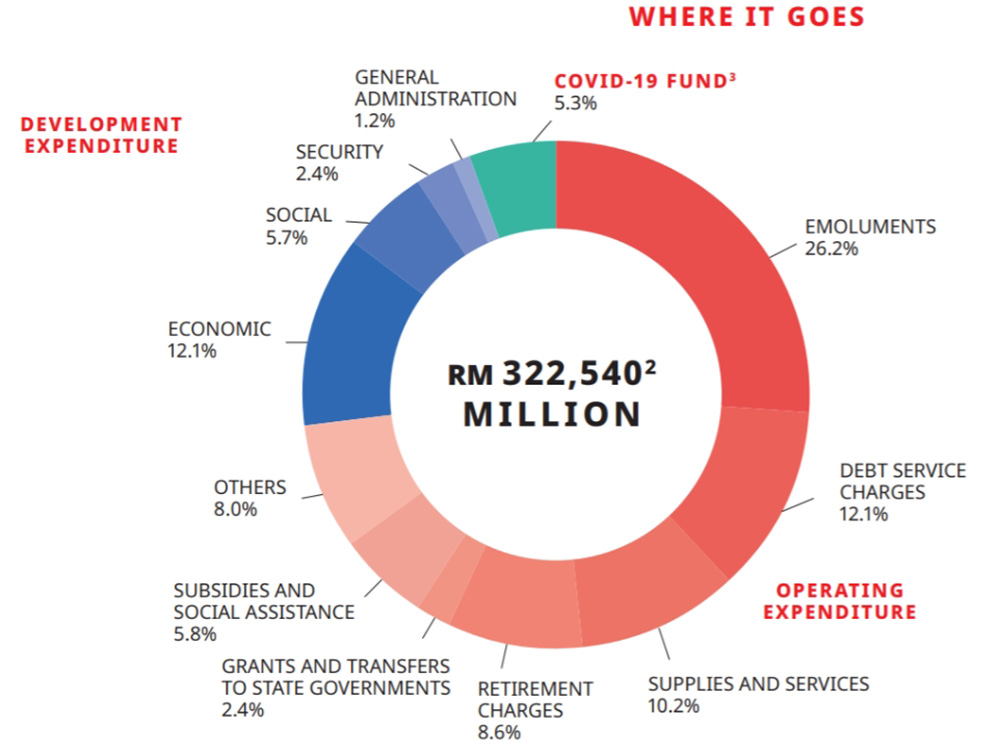

To compound further, we are boxed in by our own fiscal policy space. The 2021 budget at RM323 billion is touted the largest ever. The chart below shows how lavishly we are spending public funds.

Of the 323 billion, 73.5 percent are from revenue (taxes and non-taxes), the rest are borrowings. Please note that all of the revenue is used for operating expenditure, while we borrow for development expenditure and Covid-19. We can’t earn enough for Covid-19, but want to spend for the Community Communications Department (J-Kom).

Emoluments and retirement gobble up 47.4 percent of the revenue. Another 16.5 percent is wasted on debt servicing.

The government, by constituting an administration of 70 ministers/deputy ministers, is demonstrating how emoluments are going to skyrocket. Three ministries were created out of one under Harapan. That entails additional civil servants to service each new ministry.

We are talking about breaking the debt ceiling, and with increased costs of borrowings, debt servicing is going to hit the roof.

Development expenditure is meant for social amenities, like schools and public services like transportation. Ideally, development projects should cover the cost of funds and provide a further revenue stream.

Looking at the recent mega-projects, we have seen how development projects, already inflated, increase in costs year after year, even up to three times, not to mention leakages like in the case of school amenities, etc. So, in reality, most of our development budget caters to increased costs and leakages, to put it mildly.

Essentially our development activities are not new projects per se, yet we fund that with borrowed money and incur more debt charges.

If this is confusing, let’s ask Makcik Kiah, Puan Lee and Puan Surjit Kaur. They would tell you never to live beyond the means, just spend what you earn and save for contingencies. They know handouts are like Panadol, to temporarily relieve the pain.

They need a stable revenue-generating job or business. To invest in a new business or an upgrade, they have to undergo thorough scrutiny and vetting for a bank loan. And they know what awaits them if they request a further loan because the business failed, was mismanaged or the costs doubled. They will lose everything and be declared bankrupt.

But governments are in a very privileged position. With just a simple majority in Parliament, they can allocate whatever amount they want for whatever purposes, with no proper justification to the paymasters.

The government will never go bankrupt; the public will have to mop up the deficit through increased taxes or see the value of their money tumble, hyperinflation and joblessness.

The Budget 2021 revenue is based on a very optimistic growth scenario. In all honesty, I don’t think the government factored in the prolonged lock-down, emergency, or the economy operating on survival mode throughout 2021. An inflationary deficit budget only works when the economy operates in full steam.

It is time the politicians wake up to reality and reset the budgets. Macro statistics cannot save one for long. Creative accounting like the GST refunds will soon be found out. Otherwise, more dire ratings are expected. Public anger and disillusion, across the political divide, are bound to rise.

I have not even brought in the aspect of klepto-economics. That would kill the patient instantly!

RAMAN LETCHUMANAN was director, Environment/Conservation, Ministry of Science, Technology and the Environment (1993-2000), head of Environment/Haze/Disaster Management, Asean Secretariat, Jakarta (2000-2014), and senior fellow at S Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University, Singapore (2014-2016).