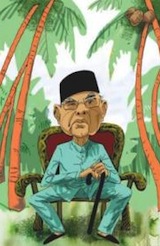

Sultan of Sulu Jamalul Kiram III continues to fight for Sabah

Jamalul Kiram III has taken his demand for the Malaysian state to be given back to his family to the next level, with deadly results

From the statements of Kiram, his relatives and Philippine government documents, there emerges the colourful history of how his family has tried to reassert ownership over Sabah. To this day, the Malaysian embassy in Manila delivers a yearly payment – the equivalent of 5,300 ringgit (HK$13,300).

South China Morning Post

When the Moro Islamic Liberation Front rebels signed a framework peace agreement at the Philippine presidential palace last October, one man in the jam-packed Heroes Hall did not join in the jubilation.

That man was 75-year-old Jamalul Kiram III, who was invited to represent the Sultanate of Sulu in the southern Philippines. He comes from a once-wealthy ruling clan that traces its lineage back to the 15th century and what is now Malaysia’s Sabah state.

Kiram was offended that neither Philippine President Benigno Aquino nor Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak had acknowledged his presence.

That royal snub, along with persistent reports of Kiram’s supporters being flogged and deported once again from Sabah, was what drove dozens of his followers to sail from their remote Philippine islands last month to press his claim.

It wasn’t an invasion, Kiram insisted, but a coming home.

“Sabah is ours,” he said, referring to the oil-rich state.

The group representing itself as a royal militia in the service of Kiram arrived by boat on February 12 to re-establish its long-dormant claim to the North Borneo area. The ensuing stand-off with Malaysian authorities erupted into violence on Friday, leaving 14 people dead.

Little of the fabled wealth Karim’s family once owned is evident in the modest two-storey house in Maharlika Village that he calls home. The village is full of refugees from the decades-long Muslim rebel conflict in Mindanao.

From the statements of Kiram, his relatives and Philippine government documents, there emerges the colourful history of how his family has tried to reassert ownership over Sabah. To this day, the Malaysian embassy in Manila delivers a yearly payment – the equivalent of 5,300 ringgit (HK$13,300).

An exasperated Kiram told Aquino: “Mr President, what more proof do you want us to show that Sabah is ours? By the mere fact that Malaysia is paying us annually in the amount of 5,300 Malaysia ringgit, is it not enough?”

Ten years ago, Malaysia’s ambassador to Manila, Mohamed Taufik, confirmed this arrangement when he told the Sunday Morning Post: “I recently paid 5,000 ringgit to the Kiram family. It’s rather miniscule – around 70,000 pesos.” He said “the rent is still being paid but it doesn’t mean we recognise” the family’s ownership.

Neither Malaysia nor Britain disputes that Sabah was a gift to Kiram’s ancestors in the 17th century for helping put down a rebellion against their wealthy cousin, Sultan Bolkiah of Brunei.

In 1878, Kiram’s great grandfather, Jamalul Ahlam, leased Sabah to Alfred Dent and Gustavus Baron de Overbeck, Austria’s former consul in Hong Kong. Both then formed the British North Borneo Company in Hong Kong and applied for a Royal Charter.

The original contract – in Malay but written in Arabic script – used the word padjak or lease, Kiram said. But the British later chose to translate it as “cession”.

This was even though British foreign secretary Lord Granville wrote in 1882 that the contract gave Dent and Overbeck merely “the powers of government made and delegated by the Sultan in whom the sovereignty remains vested”.

By the time Kiram was born in 1938, the family’s hold on Sabah had become precarious. Two years before that, his great-uncle Jamalul Kiram II had died childless. Family lore says he was poisoned.

Kiram, in a letter to President Aquino on October 15, told how the family lost Sabah: Overbeck’s “company ceded North Borneo to the British Crown on June 26, 1946.

Soon after, effective July 15 of the same year, the Crown issued the North Borneo Cession Order in Council that annexed North Borneo and Labuan as part of the British dominions”.

“This unilateral action violated the spirit of the original lease agreement,” he said.

With the death of Jamalul II, his brother Mawalil succeeded him but died suddenly six months later – again allegedly from poisoning. Mawalil’s son Esmail became sultan.

In 1962, he ceded “full sovereignty, title and dominion” over Sabah to the Philippine government.

According to then Philippine foreign secretary and vice-president Emmanuel Pelaez, Sabah was to be made part of the Federation of Malaysia in order to be “a counterpoise to the Chinese elements in Singapore” and “to ‘sterilise’ Singapore as a centre of communist infection” within the Malaysian federation.

Asserting the Philippines’ claim, Pelaez met his Malayan and Indonesian counterparts in 1963. They issued a joint communique stating that the formation of the federation “would not prejudice either the Philippine claim or any right thereunder”.

A statement known as the Manila Accord and confirming the same was issued a month later by Philippine president Diosdado Macapagal, Indonesian president Sukarno and Malaysian prime minister Tunku Abdul Rahman, documents showed.

While all this was going on, Kiram was trying to live a normal life – finishing a law degree and falling in love at 28 with 14-year-old Carolyn Tulawie. He waited until she turned 16 to marry her, according to their daughter Nashzra.

Many years later the couple later divorced amicably, and Kiram married a Christian woman named Celia. He has nine children – six with Carolyn and three with Celia.

At one point, Kiram danced with the Bayanihan, an acclaimed national folk dance company that toured the world.

He also worked briefly as a radio announcer.

Kiram’s father, Punjungan, was officially named successor and crown prince by Punjungan’s older brother Sultan Esmail.

When Punjungan fled to Sabah in 1974 during the Muslim Mindanao conflict at the time of then president Ferdinand Marcos, Kiram said he became the “interim Sultan”. But Marcos designated Esmail’s first-born son, Mahakuttah, as sultan.

Kiram once ran for Philippine senator in 2007 under the banner of then president Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo. He lost but gathered two million votes.

Because Marcos meddled in the succession, confusion has reigned over the identity of the real sultan. At one point, as many as 32 claimants emerged.

In a separate interview, claimant Fuad Kiram – younger brother of the deceased Mahakuttah and Kiram’s first cousin – said there were “many fake sultans” because they think Malaysia would pay them off.

Officially, the money that Malaysia gives is divided among nine relatives and their descendants.

Because of their numbers, each family ends up receiving only 560 pesos. In contrast, Fuad complained that “Sabah contributes US$100 billion GDP to the Malaysian economy annually”.