How Muhyiddin consolidates power through GLC appointments

TERENCE GOMEZ, MALAYSIAKINI

It has been just over a month since Perikatan Nasional took power, but the scale and scope of changes among the directors and senior management of government-linked companies (GLCs) have been bewildering. Since Perikatan is led by a prime minister and senior ministers who were in the previous Pakatan Harapan administration that made these appointments, the pace of these changes is even more astonishing.

One core dimension of Malaysia’s vast GLC world is that cabinet ministries oversee a huge range of companies. Since politicians appointed to key cabinet posts have enormous influence over the corporate sector, a brief recent history of control of these GLCs is necessary.

Ministries in business

Before the epochal general election of 2018, Harapan, under Dr Mahathir Mohamad, had promised reform of the GLCs. This pledge was important because then prime minister Najib Abdul Razak, in his dual role as finance minister, had effective control of Malaysia’s leading GLCs. This concentration of political and corporate power in the hands of the prime minister-cum-finance minister had allegedly contributed to serious abuse of business-based institutions, including 1MDB, Tabung Haji and Mara.

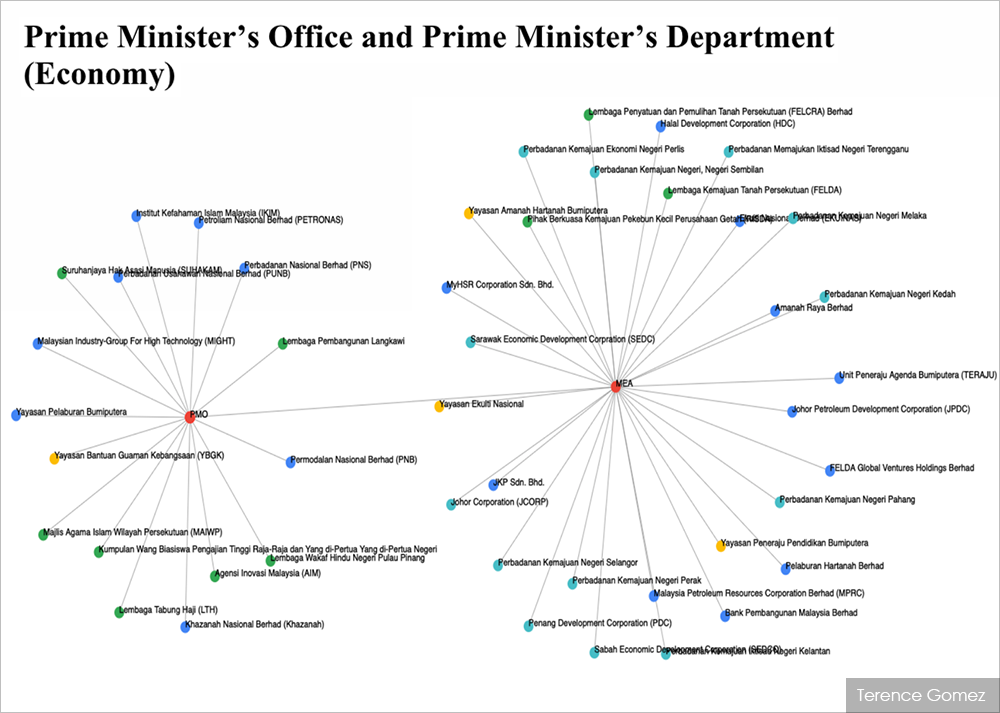

Under Najib’s administration, four key ministries had immense corporate influence – the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO), Finance Ministry, Ministry of Rural Development, and Ministry of Entrepreneur Development. When Harapan took power, Prime Minister Mahathir created the Ministry of Economic Affairs. Important bumiputera-based GLCs were transferred to the Ministry of Economic Affairs, giving the minister, Azmin Ali, then of PKR, huge influence over this segment of the corporate sector.

Mahathir also transferred Malaysia’s leading investment arm, Permodalan Nasional Bhd (PNB), from the Finance Ministry to the PMO. This meant that while the prime minister was no longer serving simultaneously as the finance minister, a trend long critiqued by opposition parties, much economic power was now situated in the PMO.

Key members of Mahathir’s party, Bersatu, were appointed as ministers of the Ministry of Rural Development and Ministry of Entrepreneur Development. Rina Harun took charge of Ministry of Rural Development, while Mohd Redzuan Yusof led Ministry of Entrepreneur Development. Both had no previous experience in government.

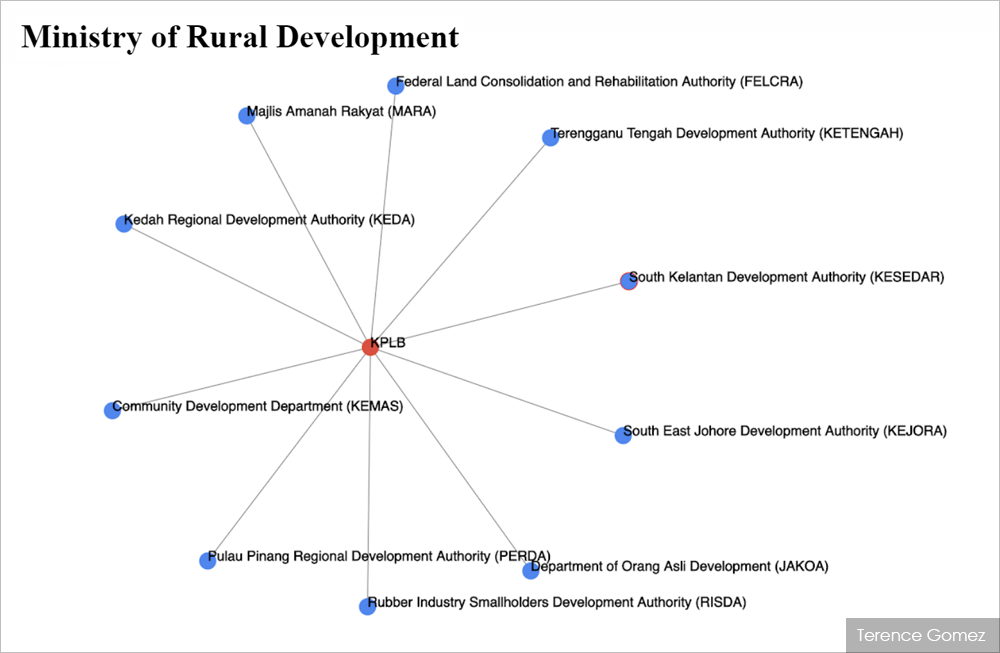

The Ministry of Rural Development oversees statutory bodies responsible for the development of rural areas where many low-income and poor bumiputeras are situated. These statutory bodies include Mara and Felcra which own a huge number of GLCs.

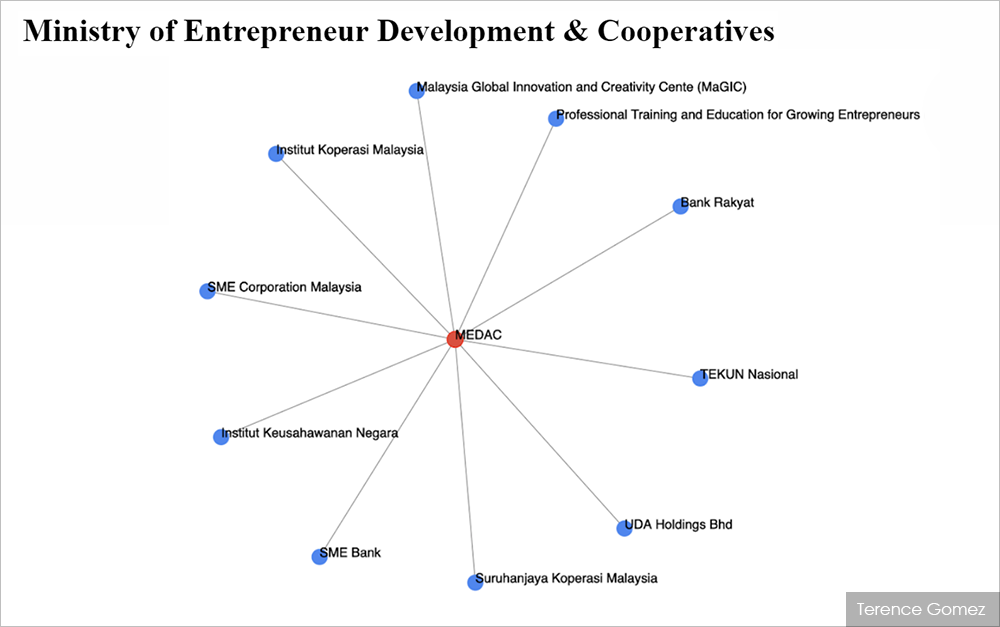

The Ministry of Entrepreneur Development oversees the small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which constitute 98.5% of the corporate sector. This suggested that Mahathir’s – and Bersatu’s – influence over corporate Malaysia, was quite substantial.

Perikatan’s power shifts

After Perikatan took power, even though Azmin, Rina and Redzuan, were re-appointed as ministers, important transitions had occurred in these ministries, as the table below indicates. The new prime minister, Muhyiddin Yassin, disbanded the Ministry of Economic Affairs and all institutions under it were merged with the PMO.

Azmin, though now a Bersatu member, was given charge of a less important portfolio, the Ministry of International Trade and Industry (Miti). Azmin was, however, appointed a senior minister. Miti does not have control of many GLCs, suggesting that Azmin’s influence over such enterprises had been diminished.

The figure below indicates the outcome of the transfer of all institutions under the Ministry of Economic Affairs to the PMO. Evidently, Muhyiddin now has even more substantial control of corporate enterprises, compared to Mahathir. Among the key institutions under the prime minister’s control are PNB and Malaysia’s only sovereign wealth fund, Khazanah Nasional.

These two institutions alone have ownership and control of eight of Malaysia’s top 10 publicly-listed companies. These firms include Maybank and CIMB, Malaysia’s leading banks, the utilities-based Tenaga and Axiata, the highly-diversified conglomerate, Sime Darby, the oil and gas-based Petronas Chemicals and Petronas Gas, and the huge healthcare enterprise, IHH.

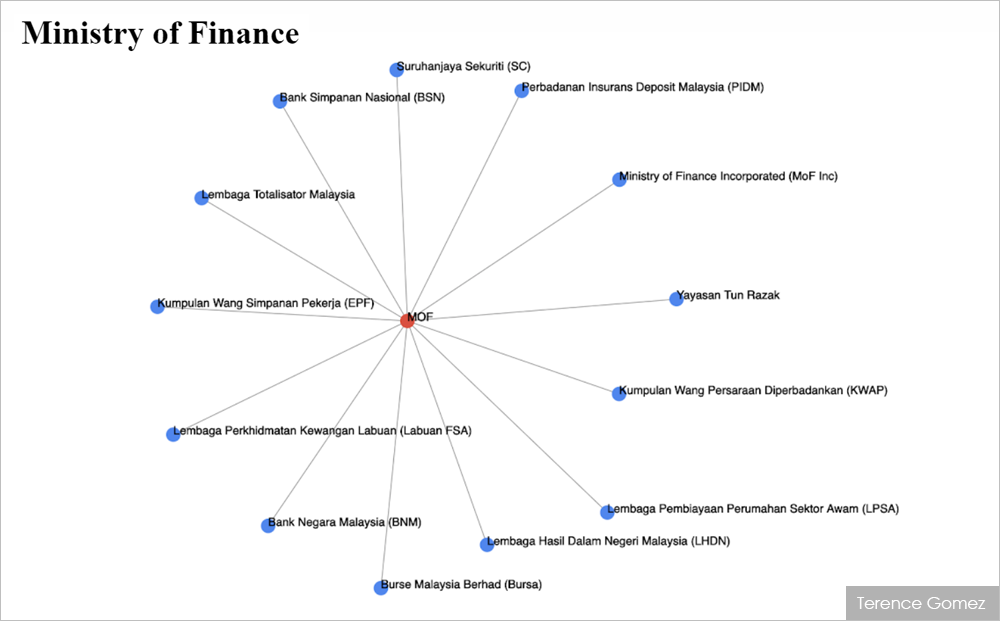

In the Finance Ministry, Muhyiddin appointed as minister Tengku Zafrul Abdul Aziz, a banker with no political affiliation. This was, ostensibly, an appointment of a “technocrat”, to help the prime minister deal with an economic downturn. Zafrul himself stressed that he was “not a politician” and voiced his hope to carry out his duties without political interference.

The immediate retort of a prominent Umno member, Bung Moktar Radin, to Zafrul’s statement was telling: “He (Zafrul) doesn’t realise that his appointment was a political move”. The Finance Ministry controls the huge savings-based institution, EPF, the public sector pension fund, KWAP, and Minister of Finance Incorporated, a key government holding company, as the figure below indicates.

Interestingly, too, although Rina had joined Perikatan, the Ministry of Rural Development is now controlled by a relatively junior member of Bersatu, Abdul Latiff Ahmad, formerly of Umno and member of parliament for Mersing, a constituency in Muhyiddin’s home state of Johor. Abdul Latiff, reputedly a close associate of Muhyiddin, has been an MP since 1999. Rina took charge of the Ministry of Women and Family Development, which has no GLC of any significance.

The Ministry of Rural Development, however, oversees a huge GLC world, as the figure below indicates. Since the Ministry of Rural Development controls statutory bodies and GLCs with enormous rural presence, major areas where Umno has long secured its support, this ministry has always been under the control of a senior party leader. It was important for Bersatu to retain control of Ministry of Rural Development since this party has little support in these constituencies.

Control of the Ministry of Entrepreneur Development was given to Wan Junaidi Jaafar, a politician from Sarawak and a member of the state’s largest party, PBB. This suggested the lack of importance that Muhyiddin accorded to the Ministry of Entrepreneur Development, which oversees the SME world. Major development financial institutions (DFIs) such as SME Bank and Bank Rakyat fall under this ministry, as the figure below indicates.

Muhyiddin would soon realise his oversight. Just a week after announcing his first stimulus package, Muhyiddin presented a supplementary package, admitting then that he had to do this in response to a serious backlash from SME-based associations. These SME associations had reacted unfavourably to Muhyiddin’s first stimulus package, claiming that without government support at least 50% of such firms would cease operating, leaving about four million people unemployed.

GLC changeovers

The enormous volume of corporate control under the PMO and Bersatu is now particularly staggering, and worrying. Meanwhile, Muhyiddin also took over as chairperson of the highly influential Khazanah, while Zafrul was appointed a board member. Azmin, who had been appointed to Khazanah’s board by Mahathir, was not removed. While it is customary for the prime minister to serve as Khazanah’s chairperson, with the finance minister also a board member, it is unprecedented for the minister of international trade and industry to concurrently serve as a director.

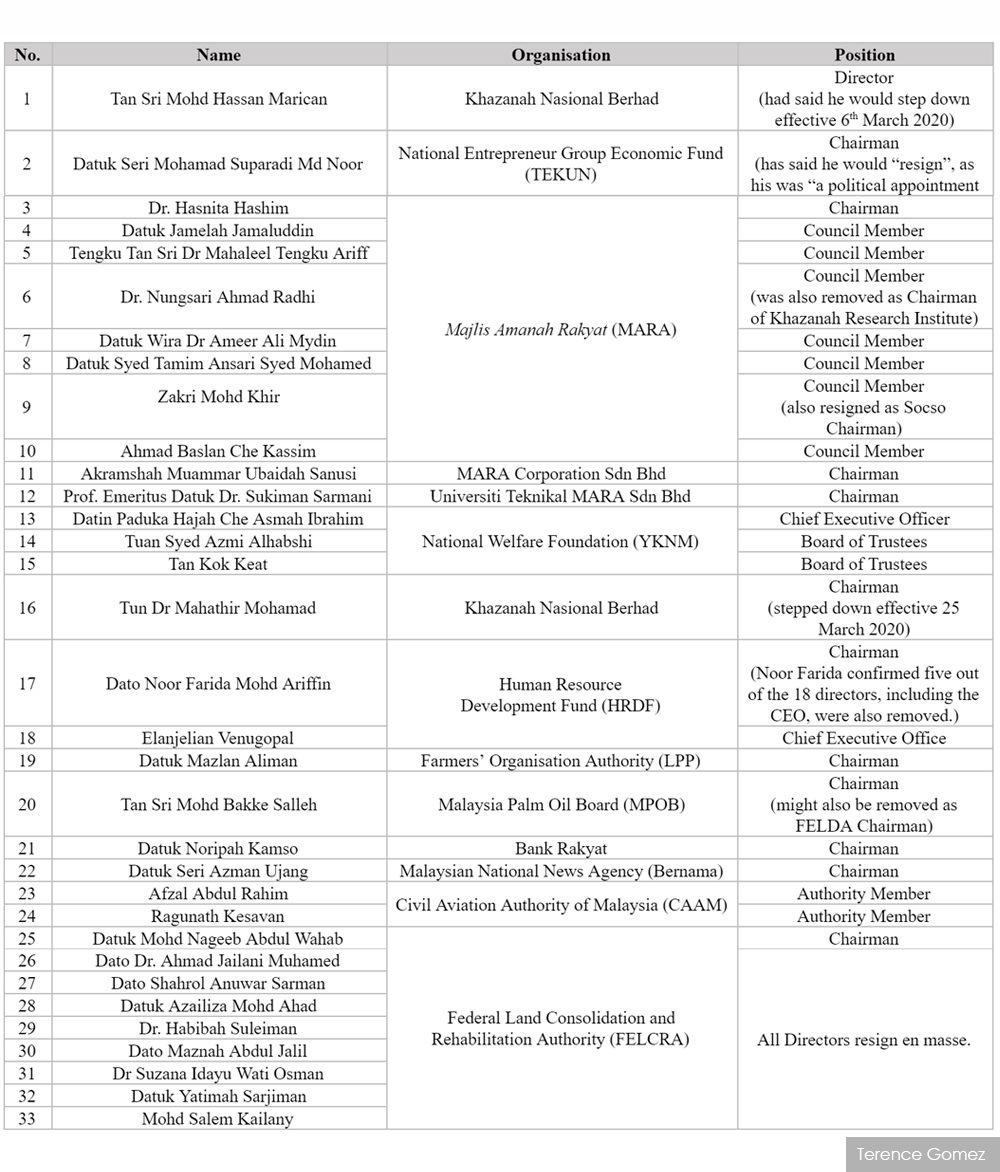

Other key board changes occurred, as the table below indicates, though some of these people had resigned on their own accord. The changes that occurred were in GLCs closely associated with these key ministries. Other important transitions occurred.

In the Human Resources Ministry, under the control of the MIC’s M Saravanan, a Bersatu member of parliament, Mohd Fasiah Mohd Fakeh, was tipped to take over as chairperson of Socso, replacing Zakri Mohd Khir, a professional from the insurance industry. However, Mohd Fasiah’s appointment will not occur because the legislation related to this statutory body stipulates that the chairperson cannot have a political affiliation.

Appointments in other institutions under this ministry went through. The Human Resource Development Fund (HRDF)’s new chairperson is Nelson Renganathan, an MIC member, who replaced Noor Farida Mohd Ariffin, a lawyer and prominent NGO member.

Conflict and change

Three key points should be noted about these issues involving GLCs. First, these diagrams do not capture the volume of GLCs controlled by these ministries. And, this is not an exhaustive list of directors who no longer serve these GLCs. The number of GLC directorships that can be dispensed to politicians is huge, a major avenue to pacify disgruntled elected representatives who have not secured cabinet appointments.

Second, even members of parties in the Perikatan coalition have protested the reconfigurations of these ministries and these cabinet appointments. Third, compounding Muhyiddin’s problems is that he has to contend with debilitating factionalism within Bersatu, at a point when party elections are imminent. Mahathir remains chairperson of the party, while Muhyiddin will be challenged for the Bersatu presidency by the influential Mukhriz Mahathir.

Muhyiddin, moreover, does not appear to have Umno’s full support, with open criticism of his ministerial appointments. Umno MP Azalina Othman Said, once a senior cabinet member, complained that her party’s parliamentarians should have been given “more significant” portfolios and that the “coalition government” should not be “dominated by any one party”.

Former Umno MP Shahrir Samad lamented that “it is as though the en bloc spirit disappeared”. Umno MP Tajuddin Abdul Rahman critiqued Azmin’s appointment as a senior minister saying that “we’re not comfortable looking at it” and that “I feel it’s a continuation of Bersatu’s agenda and maybe even more than that”.

Only one Umno leader, Ismail Sabri Yaacob, was appointed senior minister and as defence minister, a ministry with little control of GLCs. Under the Najib administration, Ismail had served as Ministry of Rural Development’s minister.

Meanwhile, Mahathir has spoken of how ministerial and GLC appointments will be used to secure crossovers to consolidate Perikatan’s control over parliament. According to Mahathir, “we had more than 114 seats (in parliament) but now that has become less” because Muhyiddin had “taken my people to his side”. Muhyiddin has, in fact, created one of the largest cabinets in Malaysian history. Meanwhile, a whole slew of GLC appointments is expected in the coming weeks.

Disturbing trends

These historical and current trends indicate that although Malaysia has had three different governments since 2018, GLCs continue to be employed in a non-accountable manner. These GLCs, created to rectify social injustices, serve instead as vital political tools for ruling elites to consolidate power.

GLCs have been used to aid the vested interests of power elites in three ways: first, to channel government-generated concessions to key constituencies to garner electoral support. Second, to allow for the appointment of politicians to the boards of GLCs to sustain party support. Third, to offer lucrative directorships to pre-empt party hopping, a point that Mahathir argues caused the fall of his government.

Since GLCs are major enterprises that play a crucial role in the economy, the need for these massive number of board changes has to be questioned as they are extremely disruptive. When GLCs have to be productively employed to prop up an ailing economy, further undermined by the Covid-19 pandemic, they remain mere tools to preserve and consolidate power.

TERENCE GOMEZ is Professor of Political Economy at the Faculty of Economics & Administration, Universiti Malaya.